The idea of walling off the border is not new to the folks in south Texas.

Threats of expansion of the wall and the seemingly continuous government presence to repair the existing sections of the wall have been a part of their reality for more than two decades.

“The government says that [the border wall] is for the public good,” said Reynaldo “Rey” Anzaldua Cavazos, sitting beside his cousins Baudilia “Lili” Cavazos Rodriguez and her brother Jose Alfredo “Fred” Cavazos. “This border wall is not for the public good. It is for a political reason.”

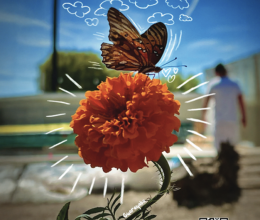

The trio are sitting on their family’s land that stretches along the sleepy shoulders of the Rio Grande near Mission, Texas. The south Texas wind is blowing hard and loud, making the wide river rough and tumble. Border Patrol boats occasionally buzz by, agents waving to the Cavazos, even stopping to chat for a bit before heading back to their shifts. The Cavazos are at home on their family’s land, as if they had grown from the soil themselves.

They have, in a way.

Jose Alfredo “Fred” Cavazos

“Well, my grandmother did buy this [land] in the 1950s when women really couldn’t own land,” explains Fred Cavazos. “So she had her sons help her with the ownership. But she’s the one who raised the money to buy this property; she used to make tamales and sell clothes. She wasn’t too educated, but she really was a real pioneer. We’ve been here for many years, we were raised here.”

Rey chimes in and explains that their extended family histories date back to Spanish settlement of the area in the 1750s. He uses a phrase commonly used by Mexican-American borderland residents: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.”

The three beam with pride at the recounting of the family’s hard-working beginnings. They all describe their grandmother as a “real go-getter,” someone who was convinced that her land purchase would sustain the family for generations to come.

Press play to hear Lili Cavazos Rodriguez speak about the history of the Cavazos family land.

But the border wall has complicated their grandmother’s dream.

It first began during the George W. Bush administration. “About 10 years ago, George Bush started to do a border wall here,” explains Rey. “We went through the same process that we’re going through now, where the government comes in, they give you papers and say, ‘You sign this so we can come in and survey your land. We’ll pay a trespass fee. And if you don’t sign, once we start building the wall, you’re going to lose this land through eminent domain.’”

“Eminent domain” refers to the government’s power to take private property for public use. It’s an old authority and one with flaws — one of the earliest Supreme Court cases refers to it as the “despotic power,” meaning it’s ripe to be abused. To check the potential for abuse, the Fifth Amendment says that private property cannot be taken without fair compensation for it.

A chair overlooks the Rio Grande on the Cavazos family property.

While private property ownership has slowed border wall construction in south Texas, the legal complexity has provided little protection for landowners like the Cavazos, though the family is currently being represented by the non-profit Texas Civil Rights Project. In a nightmarish scenario, the government has the ability to do a “quick take” of private land, which means it can take possession of private property before a court decides what the fair value is for the land and before a landowner is even compensated. In some cases, it can take years before owners get a single penny.

Now, hundreds if not thousands of borderland families are at risk of also losing their land in this way. With Trump demanding 500 more miles of border wall by the end of 2020, the administration has already illegally pilfered $9.9 billion from the Department of Defense (DOD), moving $6.3 billion into a DOD “counternarcotics” fund to build hundreds of miles of wall in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas on behalf of Customs and Border Protection. Another $3.6 billion was taken from military construction projects, including projects for military service members and their families, to be used for separate border walls.

One of the biggest, and most expensive, projects to be funded by these diversions is for 52 miles of wall snaking up the Rio Grande from Laredo up to El Paso. In West Texas, these projects are scheduled to start as early as April, with land surveyor cases already in court. For many Texan landowners, the realization that their private property could be confiscated and condemned in a matter of weeks is just starting to sink in.

The ACLU first filed a challenge to these unlawful transfers in 2019, and two federal courts said the government’s actions violated Congress’s “power of the purse” and blocked construction. In a one-paragraph, unsigned order, a 5-4 majority of the Supreme Court allowed construction to proceed pending its own review of the case. As if emboldened by the ruling, the Trump administration has threatened to divert even more money, at least $3.7 billion this year alone.

Reynaldo “Rey” Anzaldua Cavazos

The billions of dollars in diverted money is unprecedented, but the government has claimed long standing powers to steamroll construction through south Texas communities. Most notably, the Secretary of Homeland Security has used a power, granted during the Bush administration, to “waive” federal laws and regulations that might slow border wall construction.

“To me, this is a pattern of abuse,” Rey explains. “The government abuses people, especially people that cannot fight them. By the government waiving all these laws, something like 30 laws, they actually take away our rights to due process.”

The laws that can be waived include not only requirements that protect the Cavazos and their community — laws like the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts as well as the Endangered Species Act — but indigenous communities as well. “The only thing we can fight over,” says Rey, “is how much they’re going to pay us for the land.”

Many landowners, especially ones who have less access to expensive attorneys, don’t have much recourse in an almost David and Goliath type scenario. In fact, even for those who do have the means to hire a skilled attorney, many times the best they can hope for is for a better price per acre, while other landowners are often made “low-ball” offers.

Press play to hear Rey Alzaldua speak about the disparity he sees between the treatment of wealthy versus low-income landowners.

The Cavazos trio believes the system to be inherently unjust and fueled by political motivations.

“It’s just that it angers me to go through this several times,” said Rey, referring to the Cavazos family’s decades long fight to stop the federal government from taking their land. “That we lose land and sometimes we’re unable to fight for this land. And it’s unfair. It’s unfair to treat some people one way and other people another way.”

Baudilia “Lili” Cavazos Rodriguez

Lili agrees and adds another perspective, “You need to understand that if you were to grow up in a place where you know you’re safe your whole life. People don’t understand that it is safe. You talk about immigrants crossing over and they’re all bad people. They’re not bad people, they’re just trying to seek asylum,” she says with sincerity. “What would you do for your child?”

The Trump administration’s probable plan is to wall off as much of Rio Grande Valley as possible as it considers every inch of construction to have political benefits. This, in spite of land owner rights, of the flooding it will cause, and the habitats it will destroy. In late February, as indigenous leaders — and Rey himself — testified before the House Homeland Security Subcommittee about the border wall’s destruction of indigenous sites, U.S. Customs and Border Protection invited the press to witness that very destruction happening in real time.

But the Cavazos family remains firm in their resolve to protect what is theirs. Rey insists they are not going to “roll over and die.” “We’re not going to leave it to God. We’re going to fight ‘em,” he says sternly.

They are aware they might not win. But they are in their country. And this is the land that they love.

Read more about recent findings about the border wall in the 2019 update of our report "Death, Damage, and Failure: Past, Present, and Future Impacts of Walls on the U.S.-Mexico Border." The report’s findings show that hundreds of municipal and private landowners in the Rio Grande Valley, like the Cavazos, are set to lose their property.

Voices of the Rio Grande Valley: How Extremist Federal Policies Continue to Threaten Texas’ Borderlands. This photo essay is the last in a five-part series that the ACLU of Texas, in collaboration with staff and community members based in the Rio Grande Valley (RGV), published in order to demonstrate the region’s ongoing struggle to ward off intrusion of federal policies on everyday life. While many of these policies are not new to the RGV, they have been ramped up under the Trump administration, which has used the borderlands, its people, and its resources as pawns in a political game. But the people of the Rio Grande Valley are not staying silent. Read essays one, two, three, and four to explore the rich history, culture, and environment of this region in southeast Texas, and how its residents are fighting back to preserve their homes and way of life.