More from ACLU of Texas’ Humans of the Border. An interview with a Mexican journalist who asked that her name not be used.

Once, before I divorced my husband, we were stopped on the road by a man with the bottom half of his face covered, waving a pistol. At his side were men with AK-47s. I grabbed the baby and we ran, but they caught us. “Kneel down!” they ordered. Then they beat my husband, over and over.

I used to have a blog. Not anymore. I tried going to businesses to sell ads. “Ads?” the owners said. “I don’t want people to know I even have a business! I’d get extorted for money.”

Someone in a town I was in came to me and said there were eight bodies dismembered in the plaza. “You’re a journalist!” she said. “Why don’t you publish this?”

“Because I don’t want to be another body in the plaza.”

Yeah, I’m a journalist. A single, woman journalist with a child. I’m here in — well, let’s just say in a city in northern Mexico. You understand why I can’t be identified.

I’m a journalist by inheritance, willed to the work by my aunt. She was my mom’s youngest sister and she owned a newspaper. She was single and had a physical deformity that made her look odd, but to me she was beautiful, and I felt very protective. By the time I was 13 I was helping her with the paper.

She always went around with a camera, notebook, pen and mini-recorder, and her car was full of name tags that said “Press.” Even where famous stars were appearing, all she had to do was say, “Press,” show a tag, and we were in!

I started copying her at age 17, but at first I couldn’t do it right. My aunt had told me that journalism was about four questions: Cómo? Cuándo? Dónde? and Por qué? I would go up to people and recite, “How did it happen?” “When did it happen?” “Where did it happen?” “Why did it happen?” I didn’t know any better and everyone gave me weird looks. One politician told my aunt that I had “a strange interviewing technique!”

She died a few years later, from the illness that caused her deformity. I took over her newspaper. I had four reporters, all older than me.

This all happened in a town, then I moved to a bigger city and planned to transfer the newspaper there. But in order to fulfill production and ad contracts, I needed to travel the highways, and people were being kidnapped, found with their heads cut off, dismembered. One day when I was about to cover a political campaign, a friend called and said the candidate had been murdered on the road. “I can’t do this,” I told myself: they’re going after the reporters, too.”

Back in the city I’d just moved to, I went to a political event and took photos. A male reporter came up and said, “Sweetheart, there are lines here, and if you cross those lines you’re in trouble. You can’t just write. To do journalism around here you ask permission.”

Under my name I cover politics, but it’s “politics lite” — approved news, permitted news — news like the mayor fixing a pothole. I can’t do investigative work openly. Instead I get work published anonymously, in a newspaper in another Mexican city. I get quoted in the US and international press, but not by name.

Even with these safeguards, I think my phone has been tapped. When I’m driving with my kid, I always look two blocks behind me and two blocks ahead.

So why do I keep doing journalism in Mexico?

Because of my aunt. She was like a mother to me, a friend — when I was a teenager I could tell her everything. My parents were very strict. I couldn’t have boyfriends. I had one anyway, and I trusted my aunt not to tell. They absolutely forbade me from wearing tight pants. She bought me some. No makeup; she lent me her lipstick. She’d call and say, “Come over and we’ll get some gorditas.” That was code for coming over to talk.

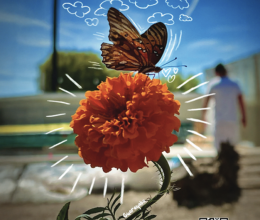

I look two blocks behind me and two blocks in front, and sometimes I hear a horn honking that sounds just like my aunt’s car. When she first died, hearing that sound made me cry.

That was several years ago. These days I dream about her. In the dream she’s always hugging me.