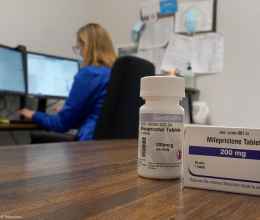

In the latest development in a fast-moving court case, on Monday the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s decision to block nearly all abortion services in the state. The ruling came after a legal challenge to Abbott’s inclusion of abortion care in a March 22 executive order instructing health care facilities across the state to “postpone all surgeries and procedures that are not immediately medically necessary.”

For Abbott and his allies, the COVID-19 pandemic is proving to be exactly the cover they need to accomplish a policy objective they’ve long held: eliminating access to abortion care.

The ruling is a reversal of the court’s April 10 decision to allow medication abortions to continue. With Abbott’s executive order due to expire on April 21, the court will likely continue to weigh in over the coming days. But this ruling represents a disturbing milestone: For the first time since 1973’s landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision, a court has allowed a state law banning almost all abortion to take effect.

The court battle highlights a new frontier the COVID-19 crisis has created in the fight over reproductive rights: Against the advice of public health experts, some states in the South and Midwest are trying to use the pandemic as a cover to ban abortion.

States across the country have issued orders to postpone non-essential surgeries and other medical procedures. Most have left it up to doctors and other health care professionals to determine what is “essential” on a case-by-case basis. Medical experts agree that abortion services are time-sensitive and fall under that category.

But eight states — Arkansas, Alabama, Iowa, Louisiana, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Texas — have used the pretext of the COVID-19 crisis to specifically target those services, claiming broad authority to order abortion providers to stop offering them. Texas, for example, has threatened to jail them for up to six months if they offer abortion care.

Lawmakers in those states claim that halting abortion services will conserve hospital resources, save Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), and slow the spread of the virus. Organizations representing medical professionals are united in denouncing the inclusion of abortion care in those states’ public health orders.

“[I]t is unfortunate that elected officials in some states are exploiting this moment to ban or dramatically limit women’s reproductive health care,” said Patrice A. Harris, president of the American Medical Association (AMA) in a statement.

Advocacy groups including the ACLU, the Center for Reproductive Rights, and Planned Parenthood have filed emergency lawsuits challenging the orders in all eight of those states.

The suits argue that the orders to shut down abortion services are unconstitutional and will cause irreparable harm to people seeking time-sensitive reproductive care during the pandemic. Clinics have already implemented social distancing measures such as spacing out appointments, they say, pointing out that far more medical resources will be used by people forced to continue a pregnancy than what would be expended in an abortion procedure.

Already, the orders have forced some women to travel to clinics in other states, burdening them with painful obstacles and provoking concerns that the restrictions could wind up facilitating the spread of COVID-19.

One 24-year-old woman who filed an affidavit in support of the Texas lawsuit said she found out that her abortion was canceled on March 23, just a few weeks after losing her job due to the pandemic. A staff member from the clinic called to explain what the state’s new restrictions meant for her.

“I started to cry, and she cried too,” she wrote. “She told me my only option at that point was to go out of state or delay my abortion and possibly be forced to have a baby. I was dumbfounded.”

Worried and uncertain of when the restrictions would be lifted, she drove 780 miles to a clinic in Denver along with a friend, rather than her partner, who couldn’t take time off of work to travel out of state.

“Obviously, had this pregnancy not been a factor, I wouldn’t be traveling during a pandemic,” she wrote. “I already felt like it was risky for me to travel to a nearby clinic in Fort Worth to have my appointment. Instead, I was forced to drive across the country, to stop at dirty gas stations, to stay in an unfamiliar home, just to get health care. I feel like Texas put me, and my best friend, in danger.”

On April 2, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, along with the AMA and 18 other leading medical experts, filed an amicus brief supporting the challenge to Texas’s order.

“The Governor’s ban on abortion in the state, except in cases of emergency, is not supported by accepted medical practice or scientific evidence in the state,” they wrote, adding, “There is no evidence that prohibiting abortion during the pandemic will mitigate PPE shortages or promote public health or safety.”

Advocates say that — just as with other measures those states have taken in their years-long campaigns to restrict abortion — public health and safety isn’t the point of the new rules, and that lawmakers are simply exploiting COVID-19 to attack reproductive rights.

“It’s not surprising that the states that are now using the COVID crisis to stop people from getting abortion care are the very same states that have a history of passing laws to ban abortions or using sham rationale to shut down clinics,” said Jennifer Dalven, director of the ACLU’s Reproductive Freedom Project.

The states that have moved to restrict access to abortion during the pandemic are among those which have passed some of the harshest anti-abortion laws in the country in recent years. Alabama, Iowa, and Ohio each passed near-total bans on abortion in the last two years, and Arkansas passed at least 12 abortion restrictions in 2019 alone. Louisiana is currently embroiled in a Supreme Court battle over a law that would leave only a single doctor eligible to provide abortion care for the entire state.

So far, the courts have blocked at least some part of the new restrictions in Ohio, Oklahoma, Alabama, Tennessee, and Arkansas – which saw its ban put on hold by a federal judge one day after the suit challenging it was filed. The states are seeking emergency appeals.

Despite those rulings, many services remain out of reach in some states, and there is little coherence to the restrictions. While Arkansas has ordered abortion services to be suspended, it continues to allow other medical specialists to exercise their judgment. Orthodontists, for example, have been permitted to schedule visits to adjust the wires on their patients’ braces, and dentists are still treating cracked teeth.

In a statement, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, along with a group of other professional medical organizations, criticized the effort to label abortion services as nonessential.

“Abortion is an essential component of comprehensive health care,” they wrote. “It is also a time-sensitive service for which a delay of several weeks, or in some cases days, may increase the risks or potentially make it completely inaccessible. The consequences of being unable to obtain an abortion profoundly impact a person’s life, health, and well-being.”