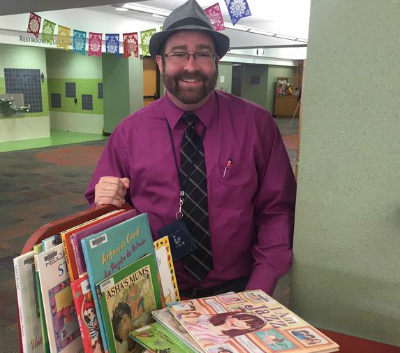

In this second installment of our two-part series celebrating Banned Books Week, I sat down with Peter Coyl, a District Manager for the Dallas Public Library.

Peter Coyl applied for his first library card when his parents realized they could neither afford nor store all the books he wanted to read. The library was a magical place for Peter, where everything he needed was right there at his fingertips, and he loved the library so much that he hasn’t left since.

Peter has worked in libraries since the tender age of 15, shelving children’s picture books at first, then working as a circulation clerk, a bookmobile driver, and a school librarian in Taiwan. For the last four years Peter has served at the Dallas Public Library, the first library in the country to introduce an online computer catalog, all the way back in the 1980s.

The Dallas Public Library is a huge and sophisticated institution, but Peter and his colleagues still have to make choices as to which books will make it onto the shelves. For the most part those decisions are based on popularity, patron requests, book reviews in trade publications, and quality. (Though Peter is quick to point out that if they aren’t purchasing items they sometimes disagree with, “then we aren’t doing our jobs.”) Additionally, the DPL is a member of the Online Computer Library Center, a global network of partnered libraries, so if a patron is looking for a book the DPL doesn’t stock, they’ll be able to fly it in from somewhere in the world.

If the DPL shelves a book a patron finds objectionable, the challenge process is at least as exacting as it is for school libraries. Most objections are made in person to desk staff, but should a patron wish to pursue it further, a form can be filled out. A staff committee then convenes to read the book and to review trade publications, book reviews and other research, at which point a recommendation is made to the Associate Director, who makes the final decision. During his four years at the DPL, only a handful of challenges have gone the distance, and none of them have been successful.

While book challenges remain a serious matter, Peter and his colleagues are at least equally concerned about other issues affecting the library: the privacy of their patrons in the wake of 9/11, the changing nature of censorship, and the evolution of the library itself as it strives to stay ahead of new technologies.

In the aftermath of 9/11, America’s librarians—not generally known as a vocal or combative bunch—went toe-to-toe with the federal government over their patrons’ right to privacy. Libraries throughout the country, including Peter’s, removed sign-in sheets for Internet access and required patrons to opt in if they wanted the library to keep track of their reading histories. In Connecticut, FBI agents demanded patron records from a handful of librarians, and then slapped them with an Orwellian gag order preventing them from even acknowledging the demand. Ultimately the gag order was lifted and the federal government dropped its case, but the attacks on individual privacy, much less the debate, are far from over.

The nature of censorship is changing as well. Thanks to the Internet, preventing people from having access to books becomes less practical with each passing day, but attempts to silence speakers are more numerous than ever. Untenured professors in fear for their jobs are redesigning their syllabi to remove anything that might potentially offend. In Connecticut, students are trying to shut down their own newspaper over a single objectionable op-ed. And the habit of succumbing to protests over invited speakers has led the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) to refer to the end of the academic year as “disinvitation season.”

Peter finds this last trend particularly onerous. He cites the case of Bill Konigsburg, an award-winning author who was invited to speak at a Houston high school about the Trevor Project, an organization that provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention for LGBT youth. Once the principal learned Konigsburg was gay, the talk was rescheduled for after school hours, all the other schools in the area had declined his visit, and he was asked not to focus on the fact that he was gay. As his mission was to prevent suicides among LGBT youth, Konigsburg naturally ignored the request.

All that said, the future of information, and therefore of the library, remains bright. Peter notes that librarians have always prepared for innovations in information technology, and embraced them. (Though he does admit they did skip the laser disc fad.)

No longer is the library a hushed and unsmiling place of sacred scholarship, but rather a place where children can be read to by their favorite authors, where half of Americans go for their internet access, a place where a community can come together and learn, and share what it has learned. “No matter how much information is out there,” Peter concludes, “people will still need libraries, and librarians.”