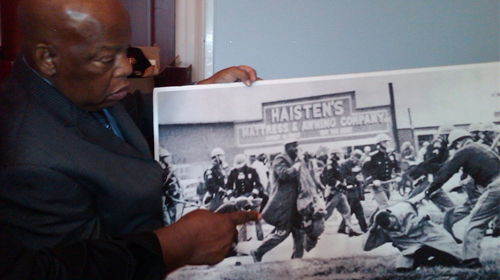

Recently, I had a meeting with Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.). I was bringing some youth leaders to his office to discuss racial justice and education. When we arrived, he starting telling us his story. We were in awe. It was a history lesson from the source itself. He talked about the events on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and showed us photos of his own beating, one of the most infamous attacks by police in history. On March 7, 1965 voting rights supporters, led by John Lewis and others, attempted a march from Selma, Ala. to the state capitol in Montgomery to present then-Governor George Wallace with a list of grievances, demanding the fundamental right to vote for all.

At that time, the U.S. Attorney General could bring suits on behalf of citizens denied the right to vote on account of race, but these case-by-case enforcement suits proved to be largely inefficient – once a practice was declared unlawful, the state and local officials would merely circumvent the court’s ruling with a different, but equally discriminatory practice. Voting rights advocates began to push for a stronger set of tools, but resistance was fierce.

On a day that would become known as Bloody Sunday, after the marchers set out, state troopers and sheriff’s deputies on horseback stopped the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, and in front of television cameras, attacked the more than 600 demonstrators by firing toxic tear gas and beating people with clubs and whips. John Lewis was bloodied and his skull was fractured. Scenes of the event were broadcast, outraging people nationwide. Eventually, with federal court protection, the marchers were able to complete their journey.

Representative John Lewis holding a photo of his being attacked on the march for voting rights March 7, 1965. Photo credit: Deborah Vagins, ACLU

On March 15, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson addressed a televised special joint session of Congress. He delivered what Congressman Lewis has called “the most moving speech ever delivered before the U.S. Congress,” saying:

At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama…. Every device of which human ingenuity is capable has been used to deny this right…. Experience has clearly shown that the existing process of law cannot overcome systematic and ingenious discrimination. No law that we now have on the books…can ensure the right to vote when local officials are determined to deny it…. This time, on this issue, there must be no delay, no hesitation and no compromise with our purpose…. We have already waited a hundred years and more, and the time for waiting is gone.

Three months later, on August 6, 1965, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act by an overwhelmingly bipartisan majority and President Johnson had signed it into law. The Act represented the most aggressive steps ever taken to protect minority voting rights.

Unfortunately, last June, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder, struck down the most powerful, and successful parts of the Act: the coverage formula that required some jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting to seek federal approval or “preclearance” from the federal government for any voting changes. The Court did so, despite an extensive congressional record demonstrating the Act’s ongoing need. Congressman Lewis commented that this decision had put a dagger in the heart of the Voting Right Act.

So instead of celebrating the upcoming 50th year of this great Act, leaders like Representative Lewis, joined by Reps. James Sensenbrenner (R- Wis.) and John Conyers (D-Mich.) and Senator Patrick Leahy, (D-Vt.) have instead led a bipartisan effort to address this injustice, with the introduction of the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014.

Although the bill is not perfect, it is an important bipartisan effort and the first step in the process to ensure the right to vote is effectively protected once again. The legislation smartly includes a rolling preclearance mechanism that is flexible, forward-looking and captures recent discrimination. While some jurisdictions with the worst records of discrimination will be initially subjected to a new preclearance formula, the legislation also provides new tools to ensure an effective response to race discrimination wherever it occurs.

On this anniversary of Bloody Sunday, as leaders of both parties join together in Selma at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, we remember all those who fought, bled, and died for the right to vote. We honor a humble leader who is still fighting for all of us today. And we pledge to work together for passage of this bill. The time for waiting is gone.

Learn more about voting rights and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.