Crystal Mason, a Texas mother of three, is on her way to a job interview but first needs to get her hair done. She stops by the Straight Line Barber Lounge, where the barber is a friend. As they chat, the TV plays in the background, announcing which presidential candidates have qualified to participate in the first Democratic Party debate. It’s a crowded field, and Crystal has thoughts. She likes Beto O’Rourke, who her daughter worked for, and Bernie Sanders.

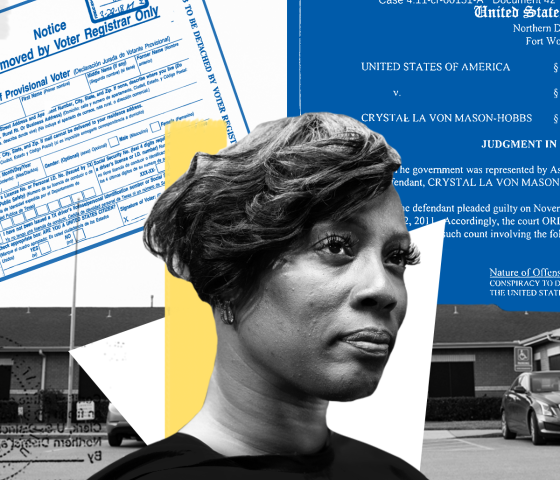

“The reason why I am for Bernie Sanders is because he reached out to me and he did a video in regard to my situation on voter suppression,” she explains. By “situation,” Crystal is referring to the fact that Texas intends to send her to prison for the crime of voting while the state considered her ineligible. About three years ago, Crystal cast a provisional ballot while she was on “federal supervised release,” a preliminary period of freedom for individuals who have served their full time of incarceration in federal prison.

It was an honest mistake that will cost her five years in prison – unless her conviction is overturned on appeal.

ELECTION DAY

It was November 8, 2016 — Election Day in Tarrant County, the third most populous county in Texas. Crystal wasn’t sure whether she’d make it to the polls in time but had promised her mother that she would try. She left work around 4:30 p.m. and drove through the rain to the Baptist Tabernacle Church in Rendon, Texas, where she had voted multiple times before without issue.

On the way, she picked up her niece Joanna, who was also going to vote. Crystal stood in line and gave her name and ID to the poll worker. He told her she wasn’t on the list of registered voters, but if she wanted, she could fill out a provisional ballot.

“He said that if I’m in the right place, my vote would count. If I’m not, it wouldn’t.”

Crystal had lived in the same house for years and didn’t have any reason to think she was at the incorrect polling location. She filled out the ballot. Unbeknownst to her, Texas considered Crystal ineligible to vote because, at the time, she was on federal supervised release after serving almost three years in prison for tax fraud. No one ever told her that she wasn’t allowed to vote until her federal supervised release was over.

THE TRIAL

Six months later, Crystal was approached by a police officer in the lobby of a building.

“Are you Crystal Mason?” she asked.

The officer informed her that she had a warrant for her arrest for illegal voting. Crystal’s first response was that there must be a mistake. She recalls saying, “No, ma'am, I didn't illegally vote. I used my ID.”

She was arrested that day.

To Crystal, and the people who knew her, it was clear this was a terrible misunderstanding. To Texas, it was an example that fit neatly into the state’s false narrative about a supposed rampant voter fraud problem, despite a lack of evidence of in-person voter fraud. Tarrant County District Attorney Sharen Wilson chose to prosecute Crystal for the crime of illegal voting, a felony in Texas that could result in a prison sentence of anywhere between two and 20 years.

On March 28, 2018, Crystal appeared before Judge Gonzalez for a bench trial. There was no jury and it lasted only one day.

The proceedings largely focused on one of four sentences that appear on the left-hand side of the provisional ballot form: “I am a resident of this political subdivision, have not been finally convicted of a felony or if a felon, I have completed all of my punishment including any term of incarceration, parole, supervision, period of probation, or I have been pardoned.”

At trial, Crystal testified that she did not read that left side of the ballot. She had been focused on filling out the right-hand side of the form, which asks for the voter’s personal information. She wanted to ensure that all the information she filled out matched her driver’s license so that her ballot would count.

She also shared that no one had told her that she was unable to vote while on federal supervised release, neither during the time she was in prison nor at any point after.

Ken Mays, who supervised Crystal’s probation officer, appeared in court that day. He testified that before Crystal began her three-year supervised release term in August 2016, they had had multiple conversations about the specific conditions of her supervised release.

He admitted to the court that his office had not warned Crystal that she couldn’t vote while on federal supervised release, according to the State of Texas. In fact, he testified that it was not a part of standard procedure to share that information. “That's just not something we do,” he told the courtroom.

Yet the state contended that despite never being told she couldn’t vote, Crystal should have known.

At trial, the prosecutor insisted that there had been “a stop sign put right in front of [Crystal’s] face.” They produced two witnesses who had claimed to have interacted with Crystal at the polling place, attempting to make the case that she had in fact read and understood both sides of the provisional ballot.

Crystal was shocked to see that the state’s key witness was none other than her next-door neighbor of nine years, who volunteered as an election judge. She couldn’t understand why someone who she shared a street with would be a part of an effort to tear apart her life. She worried it had to do with race. Hers is one of only three Black families in her neighborhood, and they have experienced hostility from neighbors over the years.

Ultimately, Tarrant County was not deterred by the lack of any plausible reason Crystal would risk returning to prison just to cast a ballot, or to the lengths she had already gone to rebuild her life since her first sentence for tax fraud.

“I came back here and rehabilitated myself,” she said on the stand. “I went to school for over 11 months and graduated. From there the whole time I was working and going to school. I have my own business now. Why would I dare jeopardize losing a good job, saving my house, and leaving my kids again and missing my son from graduating from high school this year as well as going to college on a football scholarship? I wouldn’t dare do that, not to vote."

At trial, the prosecuting attorney asked the court to “send a message to illegal voters,” and to sentence Crystal to “a stern prison sentence.”

By the day’s end, the judge found Crystal guilty and sentenced her to five years in prison.

A TEXAS-SIZED OBSESSION

In some ways, Crystal’s story is uniquely extreme. In other ways, it’s a predictable outcome of an obsession with supposed rampant voter fraud shared by Texas and much of the country.

In April 2019, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton submitted a letter to Congress, responding to a request for documents after Texas made national news for issuing an advisory that some 100,000 non-citizens were illegally registered to vote in Texas and 58,000 of those individuals may have voted illegally in Texas elections. President Trump later tweeted about it, claiming these numbers were “just the tip of the iceberg!”

This list quickly fell apart under closer inspection. Almost immediately, it was revealed that tens of thousands of individuals on the list were naturalized citizens who had been falsely flagged due to a data error. Subsequent litigation brought by the ACLU and partners demonstrated that the vast majority of the list was likely composed of naturalized citizens who were eligible to vote. In fact, the state eventually settled these lawsuits, scrapping the program because of its flawed methodology.

Paxton’s letter also claimed that his office had “real, first-person experience showing the threat to election integrity in Texas is real,” and cited as proof the “sheer number of prosecutions and convictions secured.”

However, as reported by the Huffington Post, a closer look at Paxton’s numbers show that the majority of illegal voting cases prosecuted in 2018 ended with the defendant in a prosecution diversion program, a signal that the cases didn’t merit consideration or prosecution.

To this day, Crystal, who is Black, feels that her prosecution was politically and racially charged. She brings up the case of Terri Lynn Rote, a white woman in Iowa, who was convicted of voter fraud after purposely trying to cast a ballot for President Trump twice. She received a sentence of two years’ probation and a $750 fine. Even more recently, in April 2018, a white, Republican justice of the peace in Tarrant County pled guilty to submitting fake signatures to secure a place on a primary ballot. Sharen Wilson’s office, the same office that prosecuted Crystal, agreed to a sentence of five years’ probation.

“It was to make an example out of me. It was cruel. [They] actually know that I had no intention of doing anything wrong at all,” Crystal says, pointing to these disparities.

THE CONSEQUENCES

The consequences of Texas’ obsession were very real for Crystal. Immediately, the life that she had spent years rebuilding, including holding a fulltime job while going to school and starting her own business, was upended. She returned to federal prison for violating the terms of release, leaving behind her three children and four others in her care.

“It was the hardest thing I've done to actually go back to a place that you said you would never go back to. To leave your children again. I wasn't moving forward. I was moving backwards and this wasn't supposed to be happening to me,” she recalls.

After being arrested, Crystal lost her job at Santander, an auto-finance company where she worked in quality assurance. Her son left his first year of college to be closer to home, losing his football scholarship. Her home currently faces foreclosure.

The more time that passes, the less the whole ordeal seems to make sense to Crystal. For one, Crystal did not even vote in the November election; she submitted a provisional ballot that was not counted. Moreover, the state’s claim that Crystal knew she was ineligible to vote was full of holes, resting on extremely speculative evidence. The state’s case rested on the account of two witnesses.

Karl Dietrich, Crystal’s next door neighbor, claimed that on Election Day, he gave Crystal her provisional ballot, swore her to it, and signed off on her ID. As to whether Crystal actually read the language on the ballot, Mr. Dietrich admitted that, “I cannot say with certainty that she read it.”

The state’s other witness was Jerrod Streibich, a 16-year-old whom Mr. Dietrich had recruited to volunteer at the polling place. He stated that he had initially checked Crystal in and was unable to find her name in the registration lists. It was Streibich’s first time volunteering as a poll worker.

At trial, he suggested that he knew Crystal had read all of the language on the provisional ballot because he was sitting four to five feet away from the table she was sitting at and he had “glanced” at her while she was filling out the form.

Strangely, Crystal’s attorney did not interrogate Mr. Dietrich’s possible bias or reasons for going to extraordinary and unusual lengths to incriminate Crystal, like personally contacting contacting the district attorney, an acquaintance of his, about her provisional ballot, or the discrepancies in their accounts of the day. In fact, Crystal disputes that she even spoke to Mr. Dietrich on Election Day.

Finally, her attorney chose not to call witnesses on Crystal’s behalf. Neither her mother, who encouraged her to vote, nor her niece, who accompanied her to the polls, had the opportunity to take the stand. If they had, they could have shared that Crystal never expressed any doubt or belief that she may not be allowed to vote—even after casting her provisional ballot. She fully believed she could.

THE APPEAL

After serving a little over seven months in federal prison, Crystal was released on bail. Up until two weeks ago, she was not allowed to live in her home and instead had to reside in a halfway house an hour or so away.

Crystal is currently appealing her case before the Second Court of Appeals for Fort Worth, Texas. After her criminal trial, Crystal was contacted by the Next Generation Action Network, a social and legal advocacy organization, that helped find three new attorneys to work with her, Alison Grinter, Kim Cole, and Justin Moore. More recently, the American Civil Liberties Union, ACLU of Texas, and Texas Civil Rights Project have joined her legal team. Her appeal rests on several arguments, including that she did not vote because she only cast a provisional ballot that was not counted, that she did not know the state considered her ineligible to vote, and that she received ineffective legal representation at trial. Under Texas law, a provisional ballot is not a vote. Moreover, Texas law does not specify that Crystal’s release conditions rendered her ineligible.

Even though she’s back at home now, away from the dormitory of the halfway home, the threat of returning to prison or losing her home looms heavy over Crystal and her entire family. Her faith helps her get through the days, along with journaling, a practice she started when she returned to prison, and listening to gospel music as she drives to and from job interviews.

After weeks of searching, Crystal was thrilled to be rehired by the state agency where she had previously worked. It was just the sign she needed.

“To be rehired at the same job after being honest about my story — by the government no less — this truly is rehabilitation,” she said.

Two weeks later, abruptly, a manager pulled Crystal aside and told her she was being let go. When she asked why, she was told that as a contract worker, they were not obligated to provide her a reason.

“I didn't break down and give him the satisfaction,” Crystal recalls. “I gathered my things and broke down in the car.”

She is currently searching for work. Throughout the entire experience, Crystal has leaned on her church, Friendship West Baptist, and her pastor Freddie D. Haynes, who has been a constant source of support.

“In my darkest moments, it was my pastor who was there to pray for me,” she says, reflecting on the day that Pastor Haynes drove her to the federal prison to begin her sentence.

Her spirit has also been bolstered by the outpouring of support that reached her when her story first went viral. Almost 40,000 people signed a petition for District Attorney Sharen Wilson to drop all charges. A fundraising campaign to help save Crystal’s house from foreclosure has raised $29,000 thus far.

Initially, Crystal thought she’d never vote again until she realized that may be just what Texas wants. While Crystal was in prison, her daughter got a job on Beto O’Rourke’s Senate campaign. She remembers video messaging her daughter while she was knocking on doors to get out the vote. Her daughter would say, “Hey, my mom is Crystal Mason, let's do it for her.”

That’s when she realized: She wasn’t going to stay quiet. Crystal is determined to share her story so that people can understand what voter suppression truly looks like in Tarrant County and beyond. She also wants to become an advocate for better education for people with criminal records once they return to society so that people like her aren’t set up to fail when they finish their sentences.

By sentencing her, Texas wanted to teach Crystal a lesson — that she didn’t have a vote or voice. Here’s what she says she learned instead:

“You wanted me to feel fear. You wanted me to run. You wanted me to be scared to educate and teach my kids to continue to vote, to go vote, what my mom instilled in me. Instead of letting it be a crutch, I have let it motivate me now.”