The ACLU is releasing records today obtained from law enforcement agencies across Florida about their acquisition and use of sophisticated cell phone location tracking devices known as “Stingrays.” These records provide the most detailed account to date of how law enforcement agencies across a single state are relying on the technology. (The full records are available here.)

The results should be troubling for anyone who cares about privacy rights, judicial oversight of police activities, and the rule of law. The documents paint a detailed picture of police using an invasive technology — one that can follow you inside your house — in many hundreds of cases and almost entirely in secret.

The secrecy is not just from the public, but often from judges who are supposed to ensure that police are not abusing their authority. Partly relying on that secrecy, police have been getting authorization to use Stingrays based on the low standard of “relevance,” not a warrant based on probable cause as required by the Fourth Amendment.

Records Show Widespread Stingray Use

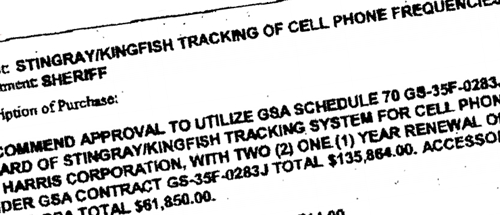

Last year, we sent public records requests to three dozen police and sheriffs’ departments in Florida seeking information about their use of Stingrays, also called “cell cite simulators” because they mimic cell phone towers and force phones in the area to broadcast information that can be used to identify and locate them. The  records we obtained document millions of dollars spent purchasing the technology and show their use in many hundreds of investigations in every corner of the state.

records we obtained document millions of dollars spent purchasing the technology and show their use in many hundreds of investigations in every corner of the state.

As we revealed last year, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement has spent more than $3 million on Stingrays and related equipment since 2008. But it isn’t keeping the technology to itself. The FDLE has signed agreements with at least 11 local and regional law enforcement agencies allowing them to use the FDLE’s Stingrays and to share them with neighboring jurisdictions. (Though the version of the sharing agreement released by the FDLE is partially redacted, a local police department near Tampa provided an unredacted copy.)

Use of the FDLE’s Stingrays has been extensive. In a May 2014 email, the FDLE identified a staggering 1,835 uses of cell site simulator equipment, likely reflecting deployment in both state and local investigations throughout Florida.

The Tallahassee Police Department (TPD) provided the most extensive information about a local agency’s use of Stingrays on loan from the FDLE, including a detailed list of more than 250 investigations in which it used Stingrays from September 2007 through February 2014. Although law enforcement agencies often justify their purchase of Stingrays—and the excessive secrecy surrounding their use — on homeland security grounds, the Tallahassee list reveals not a single national security-related investigation. Robbery, burglary, and theft investigations represent nearly a third of the total, followed by “wanted person” investigations, and then a laundry list of other run-of-the-mill offenses. The list also shows that the TPD allowed other police departments to access Stingrays, even crossing state lines into Georgia on at least five occasions.

Technology Hidden From the Courts

In many of the investigations, police never sought a court order authorizing Stingray use. In others, they sought a court order on a low "relevance" standard, but not a warrant based on probable cause. Perhaps most troublingly, the records indicate a pattern of excessive secrecy, including concealment of information that should appear in investigative files and court filings. For example, the TPD provided a sample of judicial applications and orders it says were used to justify Stingray use, but not one of them contains a single mention or description of Stingray technology. This suggests that judges weren’t being fully informed about what they were approving.

The TPD also released the full investigative files from 11 cases where the agency used Stingrays.* But officers’ notes and other documentation in the files never once mention Stingrays or provide descriptions of their use. Instead, there are only fleeting references that would likely be inscrutable to a defense attorney or judge not already on the lookout for signs of covert Stingray surveillance. Two files mention use of “electronic surveillance measures” to track a cell phone. Another says only that “Confidential intelligence” indicated the location of a phone. A fourth states that “Inv Corbett [sic] arrived and determined that [the tracked] telephone was on the second floor of the apartment.” We know from a court transcript that the ACLU successfully petitioned to unseal last year that Corbitt is the TPD officer who operates Stingrays for the department.

The Tallahassee Police aren’t alone in obfuscating references to Stingray use in case files and court documents. As we have previously reported, for example, police in the Sarasota area were instructed by the U.S. Marshals Service to eliminate descriptions of Stingray cell phone tracking in court filings and replace them with the cryptic phrase “received information from a confidential source regarding the location of the suspect.”

A new Washington Post article, based partly on the records obtained by the ACLU, provides further detail about how Stingray secrecy functions — and malfunctions — in Tallahassee. In one case detailed by the Post, prosecutors opted to offer a defendant a no-jail plea deal instead of revealing details about the Stingray as part of court-ordered pre-trial discovery. As we’ve seen elsewhere in the country, our justice system can’t properly function when judges and defense attorneys are kept in the dark about covert electronic surveillance by police.

Excessive Secrecy Persists

Below we detail our findings about Stingray use in other departments across the state, including records showing hundreds of thousands of dollars in expenditures and information on the number of cases in which they have been used. But for all these disclosures, many details about Stingray use in Florida are still shrouded in secrecy.

Several agencies refused to comply with Florida's open records laws by properly providing documents. Some acknowledged that they had responsive records, but refused to release them. The Brevard County Sheriff’s Office, for example, denied our records request in full, partly relying on a “non-disclosure agreement or requirement” with a “federal agency.” (We know the FBI has been making local agencies sign non-disclosure agreements before buying Stingrays; a fully redacted copy of the FBI agreement is likely contained in the pages released by the FDLE. The FDLE also released a copy of a non-disclosure agreement with the Harris Corporation.) The Sheriffs’ Offices in Broward and Pinellas Counties issued similar denials. Police Departments in Pembroke Pines and Port St. Lucie failed to respond to the ACLU’s request at all.

Other agencies tried to withhold records, but apparently forgot that they had already released documents on the web. The Miami Police Department responded only that it had “No departmental orders or standard operating procedures covering ‘cell site simulators,’” but did not reply to a follow-up request for other kinds of records. Documents posted on the city’s website, however, show that Miami spent tens of thousands of dollars buying and upgrading Stingrays in 2008.

And in the City of Sunrise, the police at first refused to confirm or deny whether any responsive records existed. After the ACLU pointed out that Sunrise had already posted purchase records for Stingray devices on its public website, the city saw fit to send the ACLU copies of those already-publicly available documents . . . and a request for $20,000 to cover the expense of searching for additional records.

Unanswered Questions

Not a single department produced any policies or guidelines governing use of Stingrays or restricting how and when they could be deployed, suggesting a lack of internal oversight. And no department provided evidence that it gets warrants before using the technology.

Indeed, records from Tallahassee and elsewhere indicate that police have not been getting warrants. That must change. In a strong ruling last year, the Florida Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment requires police to get a warrant before asking a phone company to track a cell phone user’s location in real time. The logic of that opinion should apply equally to cell phone tracking using Stingrays. And because Stingrays sweep up information not just about suspects, but also bystanders, the need for robust judicial oversight is all the greater.

The documents we obtained add to the growing picture of surreptitious Stingray surveillance by local police around the country. By shining a light on police practices, we hope to help bring constitutional violations and a culture of impunity to an end.

Details on Stingray Use by Departments Across Florida

Records from elsewhere in Florida show how use of the technology and secrecy about it has proliferated. Following is what we found about particular departments across the state:

- The Miami-Dade Police Department produced purchase records for hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment from the Harris Corporation, the Florida-based maker and seller of Stingrays. The Miami-Dade PD also stated that it had used Stingrays in 59 closed criminal cases within a one-year period ending in May 2014. The total number of investigations where the agency used Stingrays is surely larger, since that figure does not include cases that were still active at the time of its response. The department has a troubling history when it comes to Stingrays: according to a document available on the internet but not among the records produced to the ACLU, the Miami-Dade PD first purchased a cell site simulator in 2003 in order to surveil protesters at a Free Trade of the Americas Agreement conference.

- The Palm Bay Police Department provided records from a 2006 investigation where they used a Stingray to track a suspect’s phone. Instead of seeking court authorization or even asking for assistance from the FDLE, a Palm Bay officer “contacted Harris Corporation and utilized some of their technology and engineers to track the cell call.” This irregular procedure was possible because Palm Bay is just minutes away from the Harris Corporation’s headquarters in Melbourne.

- The Pensacola Police Department identified five cases where it used Stingrays and provided investigative files for each of them; none of the files mention or describe Stingray use. The department also stated that it “has not acquired a cell site simulator” and had no records regarding agreements with the FDLE to borrow the technology. However, the FDLE sharing agreements signed by the Tallahassee Police Department and the Leon County Sheriff’s Office both cover the “Tallahassee and Pensacola Regions,” perhaps explaining where Pensacola got the devices used in these investigations.

- The Lakeland Police Department stated that it “relies on the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to assist” in cell phone tracking cases, and produced files from three 2013 cases where it used Stingrays. Nothing in the files actually describes Stingray use. The FDLE produced a copy of its sharing agreement signed by the Lakeland PD.

- The Orange County Sheriff’s Office stated that it had no records regarding acquisition of Stingrays, but acknowledged that it had signed an agreement with the FDLE through which it could borrow the devices. The OCSO said that between 2008 and 2014 it “conducted 558 investigations in which cell site simulators may have been used.”

- The Jacksonville Police Department explained that it owns two Stingrays, but “neither of them is functional with the current technology. They are analog, outdated, of no value, and not used. Our agency has elected not to upgrade them due to the cost and frequency.” Records show that Jacksonville purchased its first Stingray device in 2001 (a “Triggerfish” model). In 2008 it used nearly $200,000 of federal grant funds to purchase additional devices, including a “Kingfish” handheld unit. The documents describe how the Kingfish is “capable of pinpointing a phone’s location inside buildings or other locations where a vehicle could not travel.”

- Agencies that signed sharing agreements with the FDLE but did not produce additional records concerning Stingray use include the Lee County Sheriff’s Office, Leon County Sheriff’s Office, and Seminole County Sheriff’s Office, among others. (See the documents released by the FDLE for the full list).

- A number of departments either explained that have not purchased Stingrays or have not used them, or stated that they did not have records responsive to the ACLU’s request, including: Cape Coral Police Department, Clearwater Police Department, Fort Lauderdale Police Department, Fort Myers Police Department, Gainesville Police Department, Hialeah Police Department, Hollywood Police Department, Lake County Sheriff’s Office, Melbourne Police Department, Orlando Police Department, Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office, Pasco County Sheriff’s Office, Plant City Police Department, St. Petersburg Police Department, Tampa Police Department, Titusville Police Department, and West Palm Beach Police Department.

* In consideration of the privacy interests of people named in the investigative files produced by several law enforcement agencies, we are releasing only those pages of the files that shed light on Stingray use, and are redacting personally identifiable information.